Regular exercise is thought to be beneficial for a variety of mental and physical health outcomes. Stress is considered anything that negatively influences the body’s homeostasis.[1] While exercise is a healthy and often stress-relieving activity, vigorous physical activity causes the body to mount a stress response. Cortisol is glucocorticoid hormone which plays a major role in stress pathways. When a stressor is perceived, cortisol is secreted from the adrenal cortex into human serum and saliva.[2] Cortisol is also secreted throughout the day to maintain homeostasis in our circadian rhythm.[3] Mounting healthy stress responses (i.e. not over- or under-reacting to stressors) may be key to living a long and healthy life.

What Happens When We Exercise?

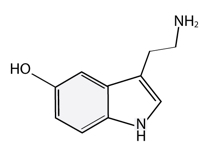

During vigorous physical activity, the body needs more energy to sustain movement and endurance. Insulin is often the hormone associated with blood sugar homeostasis; however, during physical exercise, insulin levels in the blood show little to no fluctuation.[4] Rather, levels of cortisol, norepinephrine, and epinephrine rise to induce glucose production in the liver and support cellular energy.[5]

During short-term exercise, cortisol increases if the exercise intensity reaches a certain threshold; this threshold increases with endurance training.[6] Physically “fit” individuals do not show a significant increase in cortisol after moderate exercise, but vigorous exercise will induce a substantial cortisol response.[7] Over-training and over-exercising can deplete adrenal reserves.[8] Thus, it is important for individuals to find a balance between exercising too little and too much.

Exercise, Women, and Stress

Researchers have hypothesized that women are naturally endowed with a hormonal capacity to regulate stress responses which differs from that of men.[9] Women show an increased stress response during the early follicular phase of the menstrual cycle, when estrogen and progesterone are at their lowest levels. (This is the time during the cycle when sex hormone levels most closely parallel male sex hormone levels.)[10] It is important to note that behavioral or clinical responses to stressors may be the same in men and women, but the central nervous system responses differ.[11]

Exercise and a Healthy Stress Response

One of the ways that researchers determine whether an individual is mounting a healthy stress response is to look at their “slope of recovery.” This means that they monitor the time it takes for cortisol and ACTH (adrenocorticotropic hormone) levels to return to normal after a stressor or physical challenge is over. Traustadóttir et. al. (2004) found that in older women who were physically active, or “fit”, throughout life, there was a more rapid return of ACTH and cortisol levels to normal after the stressor was over. Active, older women had a significantly steeper slope of recovery after exercising than did unfit women.[12]

Your Stress Management Goals: Consider Regular Exercise

Just four weeks of regular exercise can significantly alter salivary stress hormone levels.[13] When cortisol is too high, feelings of anxiousness, stress, low mood, and sleep issues may develop. When cortisol is too low, fatigue, inflammation, low mood, and lethargy may develop. Thus, keeping cortisol regulatory and feedback mechanisms in check is important for long-term health outcomes. After four weeks of exercise training, serum cortisol levels start to normalize in women.[14] Consider working with your healthcare provider to develop an exercise routine suitable for your specific needs.

Are you interested in finding a healthcare provider in Sanesco’s network to help with your health goals? Click here.

References

[1] Alghadir, A. H., Gabr, S. A., & Aly, F. A. (2015). The effects of four weeks aerobic training on saliva cortisol and testosterone in young healthy persons. Journal of physical therapy science, 27(7), 2029-2033.

[2] Alghadir, Ibid.

[3] Kanaley, J. A., Weltman, J. Y., Pieper, K. S., Weltman, A., & Hartman, M. L. (2001). Cortisol and growth hormone responses to exercise at different times of day. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, 86(6), 2881-2889.

[4] Del Corral, P., Howley, E. T., Hartsell, M., Ashraf, M., & Younger, M. S. (1998). Metabolic effects of low cortisol during exercise in humans. Journal of Applied Physiology, 84(3), 939-947.

[5] Del Corral, Ibid.

[6] Viru, A., & Viru, M. (2004). Cortisol-essential adaptation hormone in exercise. International journal of sports medicine, 25(06), 461-464.

[7] VanBruggen, M. D., Hackney, A. C., McMurray, R. G., & Ondrak, K. S. (2011). The relationship between serum and salivary cortisol levels in response to different intensities of exercise. International Journal of Sports Physiology and Performance, 6(3), 396-407.

[8] Viru, op. cit.

[9] Goldstein, J. M., Jerram, M., Abbs, B., Whitfield-Gabrieli, S., & Makris, N. (2010). Sex differences in stress response circuitry activation dependent on female hormonal cycle. Journal of Neuroscience, 30(2), 431-438.

[10] Goldstein, Ibid.

[11] Goldstein, Ibid.

[12] Traustadóttir, T., Bosch, P. R., Cantu, T., & Matt, K. S. (2004). Hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis response and recovery from high-intensity exercise in women: effects of aging and fitness. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, 89(7), 3248-3254.

[13] Alghadir, op. cit.

[14] Rusko, H. K. (1998). Hormonal responses to endurance training and overtraining in female athletes. Clin J Sport Med, 8(3), 178-186.

Clinical Contributor

Sophie Thompson

Clinical Support Specialist at Sanesco International, Inc.

Sophie recently obtained her degree in Biology from UNCA in Asheville. Born and raised in Asheville, her hobbies include painting, writing and spending quality time with her dog and her family.