Biologically, women experience a cycle of sex hormones throughout their lifetime, throughout the month, and even throughout the day. This biological clock has an influence on cascades of other bodily processes, including mood and behavior. Starting at the onset of puberty, women’s sex hormone levels fluctuate in somewhat predictable patterns throughout the menstrual cycle and lifetime. Thus, other bodily and psychological processes fluctuate as well.

The Monthly Biological Clock: The Menstrual Cycle

One of the biggest landmarks in the transition from childhood to womanhood is the onset of menstruation and the biological clock. While many bodily changes occur during puberty, menstruation marks the start of fertility, but also of mood fluctuations, cravings, and discomfort for some women. As girls enter puberty, levels of luteinizing hormone (LH), follicle stimulating hormone (FSH), estrogen, and testosterone increase.[i] Women are born with all their reproductive organs but these organs are not “turned on” until hormonal stimulation occurs during puberty.

In cycling women:

- FSH stimulates the follicles to produce estrogen. When estrogen levels reach a certain level, the pituitary gland then turns off FSH and produces a surge of LH.

- LH functions to stimulate the release of an egg, or ovulation. The empty follicle then produces progesterone and lower levels of estrogen as FSH and LH levels fall.

- If the egg is not fertilized (no pregnancy occurs), the progesterone and estrogen levels decline and menstruation will begin.[ii]

The Luteal Phase and The Biological Clock: A Trying Time

The luteal phase of the menstrual cycle is the period of time during which some women experience pre-menstrual syndrome (PMS). The luteal phase occurs during the second half of the cycle, before menstruation, when estrogen and progesterone levels increase and then sharply decline. Studies have found that a substantial subset of women experience mood disturbances during the luteal phase of the menstrual cycle.[iii]

Reproductive Years and the Biological Clock

While women can technically conceive once they begin menstruating, most wait until they are well into adulthood before becoming pregnant. A woman’s ability to conceive can decrease by 50% from her early twenties to her late thirties, and continues to gradually decline until around age 50.[vii] The heightened ability to conceive in young women is paralleled by an increase in sexual behavior in women between their late twenties and early thirties.[viii] After this period of increased ability and desire to conceive, the body may start to produce less progesterone.

By the mid to late 30s, many women tend to have more irregular menstruations marked by a decrease in the number and quality of follicles; the monthly biological clock begins to fluctuate. Estrogen levels often decline as well, but can also spike and have adverse bodily effects. FSH levels tend to rise in the late 30s to stimulate the ovaries to make more estrogen, but this bodily attempt is often futile.[ix]

Changes in the Biological Clock: Perimenopause & Menopause

As a woman ages, there are pronounced changes to the rhythm of her biological clock. Menopause is a term used to refer to a specific point in time; the natural end of menstruation—twelve months after the last period. Many women use the word menopause to describe the transitional state before menopause occurs, but this period is actually called perimenopause.

Perimenopause ends one year after a woman’s last menstruation, but the perimenopause transition lasts an average of three to four years before this. For some women, however, transitioning out of reproductive years can take only a few months or up to over a decade.[x] Perimenopause is an unpleasant time in the biological clock of some women, as they may experience hot flashes, night sweats, fatigue, anxiety, and depression. Ovarian function declines and both estrogen and progesterone levels fall during perimenopause. Post-menopause, estrogen and progesterone levels are at their lowest.[xi]

The Biological Clock and Neurotransmitters

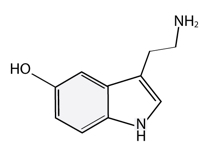

There is a plethora of bodily processes involved in the changes in a woman’s biological clock throughout her lifetime. Thus, the mood and behavioral symptomology associated with hormonal shifts may be influenced by dozens of factors. However, there are some clear links between sex hormone levels and neurotransmitter function. Not only do levels of estrogen and progesterone decline with age, but testosterone, norepinephrine, GABA, and serotonin levels decrease as well.[xii] All of these hormones and neurotransmitters (including estrogen and progesterone) have receptors in the brain involved in cognition and emotion. Periods of hormonal variability not only influence the sex hormones, but also influence neurotransmitters.

The Inhibitory Neurotransmitters: Modulators of the Biological Clock

- Estrogen has been shown to increase expression of tryptophan hydroxylase mRNA, thus upregulating serotonin synthesis.[xiii] Estrogen has also been shown to suppress GABA inhibitory input; however, progesterone mediates this effect by facilitating GABAergic transmission.[xiv]

- Serotonin and GABA work synergistically as the main inhibitory neurotransmitters; thus, the fluctuations in estrogen and progesterone during puberty, PMS, and perimenopause may account for mood and behavioral disturbances due to their effect on serotonin and GABA.

- Further, in menopausal women, selective-serotonin reuptake-inhibitors (SSRIs), are less effective than in cycling women.[xv] Therefore, researchers have emphasized the crucial role of assessing sex hormone levels before administering medications which act on neurotransmitters.

The Biological Clock: Assessment and Balance

Women have hormone fluctuations throughout the day, month, and year for most of their lives, and these fluctuations influence neurotransmitters as well. Treating the symptoms associated with female hormone imbalances is a complex process, as there are dozens of factors and neuroendocrine interactions at play. Researchers suggest that administering dietary amino acid precursors for the neurotransmitters and assessing hormone/neurotransmitter levels may be the best way to optimize health outcomes.[xvi] For more information on a woman’s biological clock, sex hormone analysis, or amino acid precursors, see Sanesco’s blog posts:

Women’s Health Initiative: Understanding the Effects of Estrogen and Bioidentical Hormones

Balancing Out PMS Signs – What to Do?

If you’re ready to start assessing neurotransmitter levels today, you can find a provider or become a Sanesco provider.

References:

[i] Mitamura, R., Yano, K., Suzuki, N., Ito, Y., Makita, Y., & Okuno, A. (2000). Diurnal rhythms of luteinizing hormone, follicle-stimulating hormone, testosterone, and estradiol secretion before the onset of female puberty in short children. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, 85(3), 1074-1080.

[ii] Publishing, H. H. (2009, June). Perimenopause: Rocky road to menopause. Retrieved January 22, 2018, from https://www.health.harvard.edu/womens-health/perimenopause-rocky-road-to-menopause

[iii] Freeman, M. P., Walker, R., Laughren, T. P., Miller, K. K., & Fava, M. (2013). Female Reproductive Life Cycle and Hormones: Methodology to Improve Clinical Trials. The Journal of clinical psychiatry, 74(10), 1018.

[iv] Freeman, Ibid.

[v] Barth, C., Villringer, A., & Sacher, J. (2015). Sex hormones affect neurotransmitters and shape the adult female brain during hormonal transition periods. Frontiers in neuroscience, 9.

[vi] Barth, Ibid.

[vii] Easton, J. A., Confer, J. C., Goetz, C. D., & Buss, D. M. (2010). Reproduction expediting: Sexual motivations, fantasies, and the ticking biological clock. Personality and Individual Differences, 49(5), 516-520.

[viii] Easton, Ibid.

[ix] Publishing, op. cit.

[x] Publishing, Ibid.

[xi] Barth, op. cit.

[xii] Rehman, H. U., & Masson, E. A. (2001). Neuroendocrinology of ageing. Age and ageing, 30(4), 279-287.

[xiii] Barth, op. cit.

[xiv] Barth, Ibid.

[xv] Barth, Ibid.

[xvi] Barth, Ibid.

Clinical Contributor

Sophie Thompson

Clinical Support Specialist at Sanesco International, Inc.

Sophie recently obtained her degree in Biology from UNCA in Asheville. Born and raised in Asheville, her hobbies include painting, writing and spending quality time with her dog and her family.